Africa's lifelines fraught with dangersINQUIRER STAFF WRITER

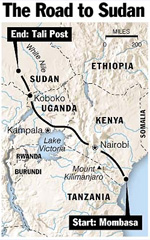

Slowly negotiating the battered and pitted two-lane road, Kuria and his cargo of American grain set off on the first leg of a 1,435-mile journey into the continent's interior. The final destination is a camp in southern Sudan for people displaced by that country's 17-year civil war. Such a trip might take two or three days in the United States or Europe, where highways are well-maintained and traffic laws are predictable and fairly enforced. But in Africa, Kuria and a second driver who will complete the final leg of the journey into rebel-held Sudan will be fortunate to finish the trek in less than two weeks. They will also be fortunate if they complete the journey without incident. Because the cargo is so precious, delivering food overland is an arduous, perilous gambit. An Inquirer reporter and photographer will accompany Kuria's load of grain all the way into Sudan, dispatching daily accounts of the African Odyssey.

Roads such as the Trans-African Highway - rutted and crumbling as it is - are Africa's lifelines. When El Nino floods in 1998 washed out a bridge near Mombasa, truck traffic was strangled and prices of food and goods soared in the landlocked interior of Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and eastern Congo. The trucks carry fuel, manufactured goods and no small amount of food aid for victims of Africa's man-made and natural disasters. More than half the food aid comes from the U.S. Agency for International Development. The trucks return bearing Africa's exports - coffee, tea, cotton and copper. The route is fraught with dangers. Kuria may encounter bandits in Kenya who plant spikes in the road to stop traffic or rebels in northern Uganda who employ kidnapped children as their footsoldiers. At every turn, ill-tempered officials can stop the truck, looking for bribes. Sometimes trucks get caught up in the outbreak of war. When rebels took control of eastern Congo in 1996 and again in 1998, some trucks were stuck at the border for up to a month while the new regime sorted out its customs rules. At night, a more insidious threat lurks in the seedy truck stops that line Africa's highway: the virus that causes AIDS. But the biggest threat is the road itself, yawning with potholes that cause drivers to veer wildly, passing each other three abreast in crazed vehicular anarchy. Those rare sections of the road that are in good repair can be just as dangerous as the bad roads. At midnight on Wednesday, a bus packed with Easter holiday travelers attempted to overtake a truck about 140 miles west of Mombasa. The driver speeded up and collided head-on with a truck carrying second-hand clothes. Sixty-nine passengers died. Three weeks ago, two buses collided in western Kenya, killing 74 people. "Yes, there are risks, but this is my work," said Kuria, 56, who is assisted on the journey by his eldest child, 21-year-old James. "I have seven children to feed, so what can I do?"

This journey actually began last year, when farmers in America's Midwest produced a bumper crop of wheat, corn and sorghum. The U.S. government, though the Commodity Credit Corporation, buys surplus grain for overseas humanitarian programs sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development. Last year USAID distributed 10 million metric tons of food to 82 countries, enough to fill 312,500 trucks like the one Kuria is driving. Food assistance programs accounted for $2.4 billion of the U.S. government's $10.3 billion foreign aid budget. America accounts for more than half the relief food distributed worldwide. Most of the surplus grain was transported by rail, barge and truck to storage elevators on the Gulf Coast, where USAID maintains stockpiles to quickly dispatch aid to emergencies. On March 5, a Qatar-flagged ship named the Farhulkhair set sail from the docks of Lake Charles, La. Its No. 5 hatch, four stories deep, was filled with 7,100 tons of golden sorghum grain destined for Sudan. Another hatch contained 700 tons of bagged red beans and 340 tons of vegetable oil packaged in 4-liter cans, also allotted to Sudan. Three weeks later the Farhulkhair passed through the Suez Canal, arriving in the Red Sea port of Djibouti on March 28, where it unloaded emergency food destined to feed drought victims in Ethiopia. On April 14, the 570-foot ship docked in Mombasa, Kenya's principal port, founded more than seven centuries ago by Arab traders and occupied at times by the Portuguese and later the British. Waiting at a berth rank with the aroma of fish and diesel were representatives of Norwegian People's Aid, one of seven international humanitarian organization under contract with USAID to distribute food in southern Sudan. For five days, the NPA representatives monitored the unloading of the ship, making sure the food did not disappear - Mombasa's port is notorious for its corruption. Tandem cranes dropped scoops into the ship's hold, removing the sorghum a ton at a time. The grain was pouring into bagging machines on the dock. The 110-pound bags - 142,127 of them - were loaded onto trucks and driven a few miles away to a warehouse. On Thursday, after the Farhulkhair finished unloading and set sail, trucks contracted by Norwegian People's Aid arrived at the port warehouse to begin loading grain to be transported to Sudan. One of the drivers who pulled up that day was Francis Kuria, who has been driving rigs for 12 years for M.A. Bayusuf & Sons Ltd., one of Kenya's largest transporters. A relay team of laborers, sweating in Mombasa's humid tropical sun, loaded Kuria's truck with 640 bags of sorghum, a grain primarily fed to animals in the United States, but desired in some parts of Africa for making bread, porridge or traditional beer. On Friday, after final repairs to his rig and Good Friday prayers, Kuria was ready to begin driving. A Christian, he expresses his faith in God with the Swahili saying painted above the windshield of his big Mercedes Benz tractor: Mungu Ndiye Waikili. God is Justice. Kuria's route over the next week will follow the trails of Arab slave-traders and 18th century European explorers, passing within sight of snow-capped Mount Kilimanjaro before crossing the Great Rift Valley where the oldest traces of human life were found. Following a railroad built by British colonialists, the highway rises to the Kenyan highlands and traverses the equator at 9,000 feet before entering Uganda. The road skirts Lake Victoria's northern shore, crossing the world's longest river, the Nile, near its source. In Uganda, Kuria will drive through the capital, Kampala, and then north through a sparsely populated savanna to Karuma Falls, where the pavement ends and vehicles stir up great clouds of orange dust from the rutted dirt highway. Parts of northern Uganda are sometimes occupied by the Lord's Resistance Army, a rebel group known for kidnapping youths and cutting off the lips of informers. Kuria's mission will end in Koboko, a village in the far northwest corner of Uganda near the border with Congo and Sudan. Koboko is best known as the hometown of Idi Amin, the dictator who terrorized Uganda in the 1970s. In Koboko, Norwegian People's Aid will transfer the grain to smaller trucks capable of driving into impoverished southern Sudan, where more than 1.5 million people are believed to have died in fighting and war-related famine since 1983. Southern Sudan, home to black Christian and animist tribes opposed to the Islamist government in Khartoum, was marginalized by the government in Khartoum for much of its history, and north and south have been at war most of the time since independence from Britain in 1955. Southern Sudan has few roads and those that it has are poorly maintained. Sudan is a vast country - the largest in Africa - and the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army controls an area of southern Sudan that is larger than Kenya and Uganda combined. Rebel-held territory includes some of the most fertile land in East and Central Africa, and if it were not for the war, it should be exporting food rather than requiring food aid. The U.S. government, which has branded the Khartoum government a pariah state for supporting international terrorists, has channeled significant amounts of humanitarian aid into southern Sudan. USAID's budget for Sudan this year is $58 million, including an estimated $35 million of food aid. Rebel territory also includes the Sudd, the world's largest swamp that confounded early explorers searching for the source of the Nile. One transporter a few years ago took a heavy truck into the Sudd during the rainy season, which begins this month, and got mired so badly he was unable to retrieve the vehicle from the mud for nine months. More than the mud can swallow a vehicle in southern Sudan. David Horsey, a manager of Truckoil Ltd., a Kenyan company that operates heavy six-wheel drive trucks that carry food into the region, said he has lost one vehicle to a landmine and another to an aerial bomb dropped by Sudanese Air Force planes. Because of the risk, the few transporters who dare to work in southern Sudan charge a lot of money - Norwegian People's Aid will pay more to haul a ton of sorghum 270 miles into Sudan than it will to carry the goods 1,165 miles from Mombasa to the Sudanese border. Ultimately, Norwegian People's Aid plans to deliver the first loads of food to Tali and Tindilo, villages that are about three day's drive into Sudan, just west of the Nile River. The aid agency operates feeding centers in those towns for people displaced by the war. In recent weeks, the Sudanese government has stepped up its aerial bombings in southern Sudan, often targeting civilian operations of aid agencies like NPA that are sympathetic to the rebel movement. Last year government planes attacked an NPA hospital in Yei, a city that has been pummeled by air since the rebels liberated it two years ago. Last week government aircraft dropped eight bombs close to a Christian-run hospital in Lui, the fifth attack there in six weeks, the rebels claimed. And just last Sunday, two government MiG-23 bombers attacked Tali last Sunday, dropping four bombs close to the Norwegian People's Aid feeding center for malnourished children that is destined to receive some of the grain on Kuria's truck.

|

© 2000, Philadelphia Newspapers Inc. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution, or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the express written consent of Philadelphia Newspapers Inc. is expressly prohibited.