Some food reaches civilians, and some goes to combatantsINQUIRER STAFF WRITER

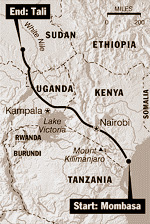

TALI, Sudan - When Monica Gajuk fled from pro-government militias three months ago, she and her family came here with a few tools, but they quickly ran out of food. Surviving on wild greens, fruits and animals, they are among the two million Sudanese who the World Food Program says are vulnerable to famine. But yesterday morning, Gajuk stoked a wood fire in her bamboo-and-grass hut and propped a metal pot on the rocks around the fire. She filled the pot with sorghum that had arrived the day before in a battered truck on the last leg of a 12-day, 1,435-mile odyssey that began April 22 in Mombasa, Kenya.

"We were forced to eat leaves and herbs because of hunger," said Gajuk, 19, who nursed her 8-month-old son between stirs of the pot. "This sorghum is much better for us than leaves." The food aid that stewed in Gajuk's breakfast pot yesterday came by one channel of many in a complex system of humanitarian aid that has built up in the last 11 years to feed famished war refugees in southern Sudan. The cargo could have been any freight following the arduous journey on bad roads that link the world's oceans with Africa's interior. In this case, it was food donated by the U.S. government to Norwegian People's Aid (NPA), a relief agency working in the war zones of Sudan's Western Equatoria region. Sorghum, used primarily as animal feed in the United States, is highly regarded in southern Sudan as the grain of choice for farmers. The tiny sorghum seeds are cooked whole with lentils or pounded and sifted into flour that is cooked with boiling water to create a doughy starch called hasida. "Before the intervention of NPA, people were dying of hunger here," said Wani Nyambur, commissioner of Terakeka County, or province. This region had been under government control until 1997, when the rebels captured much of the country and confined government troops to garrison towns like Terakeka. Much of the food aid comes into Sudan under the jurisdiction of Operation Lifeline Sudan, a humanitarian structure created in 1989 after the Islamist Khartoum government of Arabic-speaking people blocked aid agencies from delivering relief to the famine-devastated south, populated by black African tribes historically at odds with Khartoum. Operation Lifeline Sudan - an effort of the United Nations, aid agencies, and the government of Sudan - permits humanitarian organizations to deliver aid, but only with the approval of Khartoum. The Sudanese government sometimes imposes bans on air traffic into the south, and U.N. agencies stay clear of sending food to conflict areas. Norwegian People's Aid is controversial because it openly sympathizes with the rebels rather than taking the neutral position of most humanitarian agencies. It does not subscribe to Operation Lifeline Sudan, and so it works in areas close to the war zone, like Tali. Its chief donor is the U.S. government, which has sought to isolate the Khartoum government. Last year, congressional supporters of the Sudanese rebels passed a law allowing the U.S. government to give food and medicine directly to the Sudan People's Liberation Army, causing a flap within the humanitarian community. Some aid agencies protested, saying that if the U.S. government gave direct aid to the rebels, it would imperil the neutrality of all humanitarian workers. The Clinton administration decided to withhold direct aid to the rebels. But the distribution of food aid here in Tali, where soldiers live among their families and where sharing is deeply ingrained in the culture, demonstrates that no clear line exists between delivering aid to civilians and soldiers. Although Norwegian People's Aid says it tries to monitor the flow of food, the food disappears into the population as a drop of water evaporates when it hits hot pavement. NPA says it has targeted 24,000 people here for aid, but distribution is handled by the Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Association, the humanitarian wing of the armed rebel movement. Food is allocated to village chiefs, who distribute it among their people. Rather than 24,000 people getting half-rations of their monthly food requirements, the food is actually spread more thinly across a population three times as large. In the past, the rebels extorted a share of the food. In recent years they are said to request "voluntary" contributions from village elders. The fact that some of the aid ends up with combatants - or makes more locally grown food available for the army to acquire - does not bother NPA officials. "We've had a lot of debate about humanitarian aid and neutrality," said Daniel Eiffe, an Irish former priest who heads NPA's office in Nairobi and is a prominent pro-rebel activist. "No aid is neutral. There's no question if you bring 10,000 blankets in, a couple thousand of those will get to the soldiers." But some of the aid also reaches civilians, as was plain yesterday in the complex of three huts where Monica Gajuk and the nine other members of her family live. Gajuk said the food would last her family only four or five days. One of her brothers is a soldier at the front, and she said the rest of the men needed the energy from the food to plant crops that will feed them four months from now. "The food is OK," she said. "But it would be better if it were in greater quantities."

|

© 2000, Philadelphia Newspapers Inc. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution, or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the express written consent of Philadelphia Newspapers Inc. is expressly prohibited.